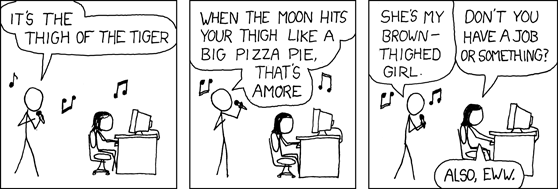

Warning: serious business in a very silly disguise ahead.

You will of course remember that logistics is all about the five rights: getting the right goods, in the right quantity, to the right location, at the right time, at the right price. (And if you don’t, you could read all about it in my March article on the five rights.)

But now imagine the following scenario (perhaps a bit too literally a scenario, but please humour me).

You are the logistics coordinator for a nutritional NGO in the Kingdom of Far Far Away. After a rather nasty little conflict about a swamp, large groups of displaced people have moved to the edges of the disputed area, where spontaneous IDP camps have appeared. As there is hardly any food available there, levels of malnutrition rise alarmingly (and there there have even been some unconfirmed cases of cannibalism amongst one of the tribes, the Jinjabredmen). Your NGO has decided to intervene and you are tasked with finding sufficient amounts of the local staple, faerivloss.

You have two possible sources for the faerivloss:

- You can buy it in the capital for about 200,000 shrec/MT (about $800/MT). Transport by local truck (affectionately called ‘donkeys’ because of their usually greyish colour, their ability to where even stallions can’t, and their drivers’ propensity for Eddie Murphy impersonations) will cost you an additional 30,000 shrec/MT.

- You can get the faerivloss for free from the local sub-office of WFG (the World’s Fairy Godmother) who just received an enormous donation of the food from the Republic of Dizneeland (halfway across the globe). The donation is sitting in warehouses in the main harbour, but the government of Dizneeland offers to transport it for free to the IDP camps using a number of MH-53E Sea Dragon helicopters, stationed on a carrier just of the coast.

Not a difficult choice, isn’t it? Both options give you the right goods, in the right quantity, at the right location, at the right time; but the donation gives it to you for a price that is much righter than the locally bought goods. So you quickly fill in the WFG requisition forms and go off for a beer.

A couple of years later, you return to Far Far Away as part of your organisation’s emergency team. Although the IDP’s have all returned home after the resolution of the conflict and the accession of the new king (as the result of the unfortunate anuration of the old one), the region again is in the grip of a famine, and you quickly find out why: after the importation of massive amount of free faerivloss, the price on the local markets collapsed and the local farmers were forced of their land (and have moved to giant slums in the capital, where they joined the former donkey drivers, who now try to make a precarious living by driving taxis or, if they are lucky, work as drivers for the numerous NGOs that have made their base there). Most of the land lies fallow, and there will be no faerivloss harvested for the second year in a row. Complicating matters is that the local harbour is rendered largely unusable due to a number of very destructive hurricanes – probably the result of global warming.

Suddenly you get a sinking feeling in your stomach; similar to what you felt when, as a five-year-old, you pulled the tail of what you thought was the neighbour’s cat, but turned out to be some strange feline wearing boots and a rapier, speaking Spanish-accented English.

Of course, in reality our decisions will normally not have such dramatic consequences – but each of our decisions could have smaller but still noticeable negative consequences. When you import goods from overseas, you will have an impact on the local economy, and transport will have an impact on the global environment. And, of course, the fact that your NGO does not need to pay for the donated goods or their transport, does not mean that those costs have not been incurred.

Normally it is not up to us logisticians to make the decision whether we would forego a possible advantage for our organisation, based on wider-ranging considerations like climate change or economic consequences. However, it is up to us to make the people who do take these decisions aware of the possible consequences of our logistical choices, and ensure that they know that there is more than just the one option.

{Continue Reading 4 comments }Aid and aid work, Logistics, The light(er) side