Scenario 1: a house in your town catches fire, killing one person and making 5 people homeless. As the logistics officer of your town’s emergency services, you are in charge of the logistics support for the initial response as well as for the physical support of the newly homeless people.

Scenario 2: you are still that town’s logistics officer, but now a gas explosion rips through an entire block. Ten people are killed instantly, tens are seriously wounded, and scores are made homeless.

Scenario 3: you did well in the previous two cases, and have been promoted to your state emergency services’ logistics position. Three days after you start your new job, a number of bush fires break out under very hot, dry, and windy conditions, and converge on your state’s capital. More than a hundred people are killed in the next three days, several hundreds are seriously wounded (swamping the hospitals’ emergency, IC, and surgical departments), and almost a thousand people are now without homes.

Scenario 4: as emergency logistics coordinator at your country’s ministry of internal affairs, you are confronted with a devastating earthquake that destroys large parts of the capital and trashes the main harbour and the two airports. First reports indicate over a thousand casualties, untold numbers of wounded, and up to a million people who are living in the streets under improvised shelters.

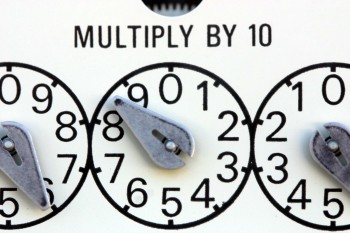

The impact of these four scenarios more or less follows a logarithmic scale: each is about ten times as big as the previous one. Does that mean that the logistics for each is ten times as difficult as the scenario that precedes it? Nothing like it: organising the logistics for scenario 2 will take considerably less resources than ten times scenario 1; but scenario 4 will take considerably more than 1000 times as much to respond to at the same level – and organising its response logistics is probably several thousands of times as difficult. In fact, it becomes a practical impossibility to offer the same level of response: there is no way that we can give all those casualties dignified burials, all those wounded top-notch medical care, get everyone who is made homeless under a solid roof within the day; even if we would have the resources to do so.

The reason for this can be illustrated with the analogy of a crossroads. Where two busy four-lane streets intersect in a four-way crossing, traffic can be controlled by one traffic controller (not efficiently, perhaps, but safely). A five-way crossing is suddenly a lot less easy to control: you would probably need at least two controllers. Now imagine what would happen if town planners would be crazy enough to allow an eight-way crossing. You would probably need four or five traffic controllers to do this well, and coordination between them would be more than a bit difficult, if not impossible.

Yet emergencies aren’t planned, they emerge; eight-way crossings and all. This is what makes large-scale emergency response so extraordinarily difficult, and why doing this well cannot be measured by the same norms as the response to smaller-scale emergencies: complexities of scale trump everything.

[Image by Chance Agrella @ Freerange Stock.]

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

I like the new layout. Interesting post.

Thanks, Tielman!